I was struck by a tweet this morning regarding the difficulty with handing out XP awards for exploration and roleplaying, specifically, that such rewards are arbitrary and hard to rightsize. This immediately struck me as a very valid complaint, but also one that's very easily addressable - it's just a matter of identifying the behaviors and experiences to reward, then plugging them into the reward system. For illustration, I'll be using 4e to show how to do this (primarily because it's standard reward model is very robust) but the basic idea can be used for almost any XP-driven game, especially ones with the idea of an encounter.

For purposes of awards, I'm going to provide a loose definition of both roleplaying (as a specific subset of play) and exploration. RP is, practically, engaging some element of the setting. This may seem like a strange definition if your first thought is that it's talking in a funny voice or getting very emotional at the table, but those are just ways to go about engaging the setting - that is, ways to meaningfully interact with the setting as if it matters. This can range from involved conversations with NPCs to hard choices about the fate of nations.

Exploration is a little bit easier to quantify - it's the process of adding something to the mental (and sometimes physical) map of the campaign. When the players explore The Dungeon of Doom then they get certain rewards just for being there (assuming that there are fights and challenges in a place called The Dungeon of Doom) but they have also added TDoD to the landscape. In the future, new enemies might take it as a lair, or maybe people will try to reclaim it. It's now a

thing, and that makes it part of the campaign. Exploration is the process by which these things (which might properly be people, places or things) get added to the game.

These two elements may seem difficult to standardize for rewards, but they share a common idea which can tie this all together. Both rotate around the idea of campaign elements - either engaging them or adding them - and it's not difficult to systemize that. All it takes is a list.

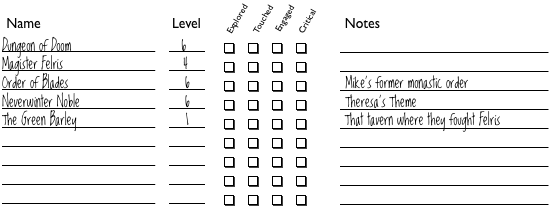

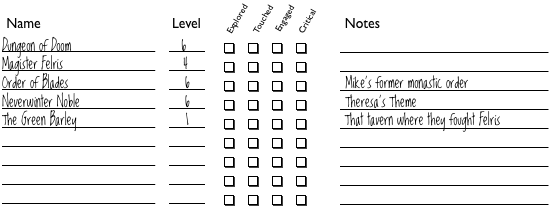

I'm going to call this list the Game Log for simplicity sake, but the name isn't important. What matters is that it's a list of the elements that come up over the course of a campaign. It will grow over time, and it provides a valuable resource for GMs, both to handle XP awards and to provide a little inspiration when designing adventures. The log looks like this:

(You can download a PDF of the form

here)

Using the Form

The Name column is for the name of the element. Elements might be anything that can recur in a game, limited only by the taste of the GM. This includes locations, NPCs and organizations, but it can also include character elements. Themes (as presented in the Neverwinter campaign setting) are another great example of a possible element.

Just keeping a list like this is useful to an GM, and most of us already keep it in one form or another, if only to answer the "Ok, who was that guy with that thing that one time?" kind of questions that pop up during play.

The level is a little bit less obvious. While it's tied to the idea of character level, it does not have exactly the same meaning. Practically, level is a measure of how important an element is, with the most important elements having a level equal to the current level of the characters. Mechanically, this is tied to XP rewards (we'll get to that in a second) but it also is a useful way to keep track of what is an isn't used in a campaign.

Generally speaking, when an element is introduced, it will probably be at the character's current level. It may "level up" any time it is engaged (see below) but it shouldn't go beyond the character's current level unless it's something the GM really wants to emphasize. That's the default assumption, but there are a few tricks that can be played - GMs looking to experiment in allowing players to introduce elements in play may allow them to do so, but start those elements out at level 1, and force them to grow in importance through play.

The checkboxes are for use in play, to indicate what's happened. "Explored" is the most straightforward - you check that box the same time you add something to the list (or, if you already had it on the list, when the players first encounter it). An element should only be explored once in its lifetime, so once this box is checked, it stays checked.

The other boxes - Touched, Engaged and Critical, see a bit more action. When an element comes up in play, you check the box that corresponds to how it came up.

If it was a memorable but unimportant part of play, then check "Touched". This is appropriate if an NPC was visited, a scene happened at a particular location, or the players talked about a thing.

If it was a noteworthy part of play, then check "Engaged". The line between touched and engaged is a bit subjective, but that's an intentional nod to GM taste. In general, something should be considered engaged when it provided a strong motivation for play or created a cost or a choice. If the players had to have an extended negotiation with an NPC or their favorite bar burned down, that would be engaged.

One trick that comes in handy is looking where else rewards are coming from. if the negotiation with the NPC is also a skill challenge, then the negotiation itself may not merit an Engaged tickmark (though it probably merits a "Touched") but if the skill challenge _also_ engages the players and characters, then yes, it totally merits a check.

"Critical" is like engaged, but moreso. If the interaction is particularly central to play, or is a turning point in the campaign, then Critical gets checked. The GM will probably know when a Critical interaction is coming, since it's usually a result of the GM doing something awful to or with the element, but it's possible to be surprised, and this is what to check if your players really blow you away.

The notes field is, as you might expect, where you keep notes. Hopefully self explanatory.

The Form and Rewards

At the end of a session, you should have a few checkmarks that indicate the things that your players found and engaged. Turning that into a reward is based on the idea of a standard award, and this is why I use 4e to illustrate.

The standard award is an amount of XP equal to that given for a monster of a given level, in this case, the level of the element (I told you that would come in handy). The basic idea is that an "Explore" or "Engaged" checkmark gets the standard award, while a "Touched" checkmark awards a fractional reward, and a "Critical" result provides a bonus. In 4e terms, these line up roughly with a minion and an elite (so 1/4x and 2x respectively).

Thus, for example, let's say that the players interact with a level 4 elements.

For discovering the element, they gain 175 XP.

If they touch on it, then the award is 44 XP.

If they engage is, then the award if 175 XP.

If engagement with it is critical to the game, then the award is 350 XP

Note - Only give the highest award, though you may give an exploration and engagement award if both seem warranted.

Run down the list, tally the awards, pool them, then divvy them among the players. Simple as that.

Notes and Thoughts

Exploration Games: You can change the proportions a bit if you want to emphasize or de-emphasize exploration. If exploration is critical to the game, then the reward for an explore tick might be as much as 5x a standard award.

Long List: So, what keeps the list from getting crazily long? While GM editorial oversight (especially the decision whether or not something goes on the list or not) plays a role, then I suggest the following trick: After an element gives its exploration award, drop its level to 1, and let it level back up in play. This means that players will get better rewards for working within a smaller list than they will by constantly having things get added, which nicely simulates the conservation of characters and locations you see in most fiction. It also provides the GM a handy tool that reveals which elements the players actually care about based on which ones get leveled up.

Personal Awards: Note that this model explicitly rewards the entire group equally for roleplaying, and I admit that's something I very strongly endorse, but on the off chance that you want to reward star players, then it's a fairly simple matter of noting the star performer in the notes column, then not adding the reward for that element to the pool, and give it directly to the player.

Slightly more complicated is the issue of personal character elements - that is, should everyone get rewarded when a given character's theme becomes important to play. My answer is a profound "yes", but if that is not to your taste, then you may consider some elements to be "owned" by a specific character, and have the reward go directly to that character rather than into the pool.

But I really suggest against it. Not only does it introduce the bookkeeping hassle of mismatched XP and the social hassle of rewarding the loudest players, it removes the incentive for players to celebrate each others awesome. If only you get rewarded for your character theme, then only you will look for ways to hook it in. If everyone is rewarded for it, then everyone's looking to bring it into play. That's a vastly preferable arrangement in my mind.

Other Systems: As noted, while it's easiest to do this with 4e, if you can figure out the standard award for your game, the model translates easily enough. Heck, you can even do thematic versions. For example: for a white wolf game, I'd forgo levels in favor of rating things from 1-5 dots and just be a little more stingy about how they level up.